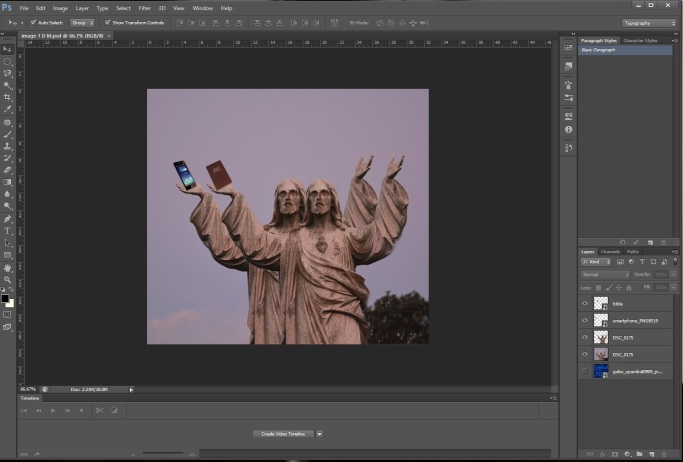

Final Image 1

(Nikolic 2016)

“1 Like = 2 Prayers” explores how the practise of blind faith as a social ritual has been altered through the changing digital landscape of the internet. Particularly this piece aims to communicate the relationship between old media in the forms of communicating religion verbally and through traditional practices, versus the pressure certain users feel to maintain these traditions through the utilisation of new media systems such as social media. The caption and the surrounding imagery refer to examples of the numerous Facebook posts that ask people to comment or like a photo which showcase an unfortunate situation such as a starving child or a picture of war, in order to send a prayer virtually to those pictured. Ultimately the dual forms of Jesus in the image, act to reiterate the fact that digital media as a social norm is powerful enough to alter even the longest standing traditions available to humanity. Similarly, the text plays on the fears of those who are scared of technological change. This is done by showcasing that even things that some view as sacred such as the holy bible can be replaced by an object such as the smartphone. Ironically users who do practice faith within the traditional and digital parameters know that the experience is a subjective one and that holding such fears would be irrational and available only to those who are not digitally literate and who wholeheartedly believe that “one like equals one prayer.” Additionally, the piece raises the question: do those who practise traditions following a certain faith need to adapt their practises digitally and if so is this form of digital prayer detrimental to those religious movements?

The final image was created using Photoshop, a photo editing software that allowed me to experiment with particular tools and compositional techniques such as layering images together using the layer function, placing text on top of images and contrasted colouring effects through the use of the outer glow special effect tool. However, prior to compositing the final image, I created two earlier versions of the image, one which was heavily based on remixing Ary Schaffer’s painting titled Greek Women Imploring at the Virgin of Assistance (1826). My decision to re-draft the concept for the image was due to ethical issues surrounding copyright and the issue of repurposing a popular painting without a creative license and claiming it as an original piece of work. Secondly, because the assigned assessment brief specifically mentioned a preference for us to not only composite the image in a photo editing program but also produce an image with a device such as a camera or a smart phone, I resorted to choosing an image I had taken with my camera depicting a statute of Jesus at the Bondi cemetery. In doing so, I have complete ownership rights to the image and this grants me further freedoms due to the ownership rights I possess over the image.

Reference

Scheffer, A. 1826, Greek Women Imploring at the Virgin of Assistance, Google Art Project, viewed 9 October 2016, < https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ary_Scheffer_-_Greek_Women_Imploring_at_the_Virgin_of_Assistance_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg>

Final Image 2

(Nikolic 2016)

“You Are Your Own Informant” depicts issues surrounding privacy and surveillance that arise when users choose to share their personal information online. More specifically the image communicates that through the normalisation and everyday use of social media websites such as Facebook, users often forget that most of the information available to governments and businesses online have been made available by the individual users themselves choosing to freely publish information about themselves online. The accompanying text reiterates this message as it reinforces the idea that the digital landscape has made it easier for breaches of privacy to occur because more often that not we point the spy glass towards ourselves through the use of our own camera lenses. Additionally, by being distracted by the convenience of sharing information and having conversations about our personal lives with the social web of friends we have on Facebook, we often need to be reminded that within the digital parameters of the internet nothing can stay hidden or be hidden. Stylistically the choice to use a selfie of myself aiming the camera like a gun to my own personal details that I have freely shared on Facebook, such as a picture of my face, information about where I live, where I was born and where I study, visually depict the dangers of freely exposing information about myself on the internet.

The foreground image was taken on my DSLR camera, however the coding in the background is a screenshot that was posted on an IT blog titled: unmaskedparasites.com. Ethically I feel that I have repurposed the image heavily into my own work, however due to copyright issues I would be required to ask for permission to use the picture if I were to post the image online as my own work. The reason why I chose to use this image was because I found it difficult to recreate a believable line of coding in Photoshop, in particular replicating the style of font used was difficult and made the image not as believable.

By working with a number of layers I separated the background from the original image using the Magnetic Lasso tool in order to make the camera the focal point of the image by making it larger and separating it from the background so that it would starkly contrast the blue lines of code. Secondly, through the creation of a clipping mask I was able to insert another image into the camera lens and then drag the supporting rectangle text bubbles taken from my Facebook profile. As for the placement of text and the black framing I had to resize the image and layer a black background behind the image. The use of a black frame with contrasting white font serves as a vector that guides the viewers eye firstly to the camera lens and then to the rest of the image. The use of this framing becomes effective to the overall composition of the image and it further replicates the framing of a polaroid picture reversed to further communicate the idea of a frame within a frame.

Reference

2009, ’10 FTP Clients Malware Steals Credentials From’, Unmask Parasites Blog, weblog, viewed 22 October 2016, < http://blog.unmaskparasites.com/2009/09/23/10-ftp-clients-malware-steals-credentials-from/>.

© Sourced from Wikipedia

© Sourced from Wikipedia